How can we study the emergence of information in the lab?

Given binary digits (or ‘bits’) 0 and 1, we can encode our 26-letter alphabet, and its extensions, from infant babbling “ba-ba-ba,” to Hamlet’s contemplation on life or death. To encode our alphabet, let the 5-digit string 00000 map to the letter ”A,” let 00001 map to “B,” and 00010 map to ”C,” and so forth up to 11111, or 32 possible 5-bit strings. These 32 strings encode the 26 letters from A-to-Z, as well as breaks and punctuation; then any word or phrase can be encoded as a sequence of bits.

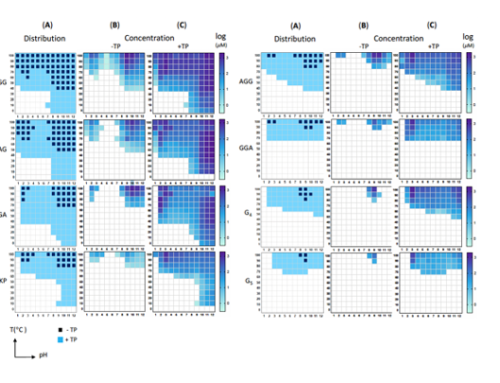

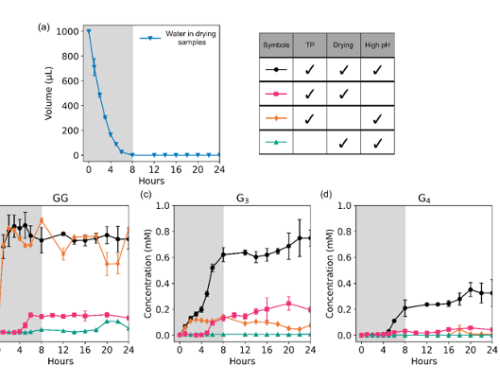

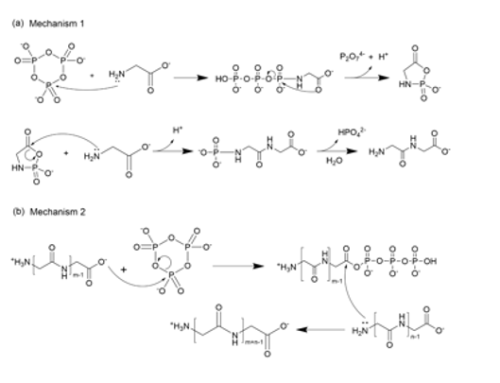

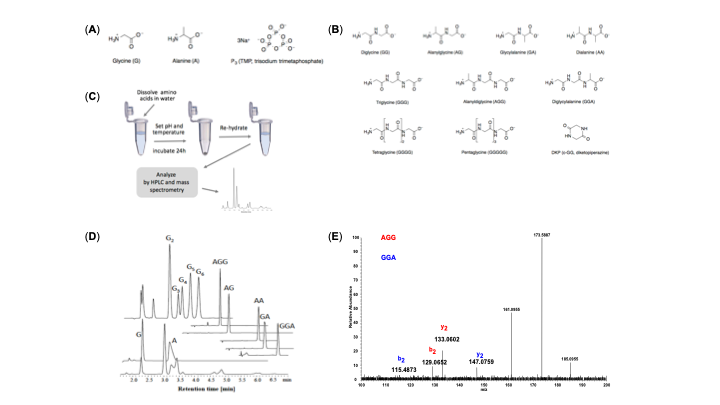

In the laboratory, simple amino acids glycine(G) and alanine(A) act as bits 0 and 1. We explore chemical reaction environments where G and A can unite to form stable strings, starting with two-digits (GG, GA, GA, and AA), and growing longer. We use tools of chemical analysis to separate and study the resulting products. These sequences and their amounts depend on how the original two amino acids react; in this sense the distribution of products encodes information of conditions needed for their emergence.

Here are more details: (a) Structures of starting amino acids (glycine, L-alanine) and the activating agent, trimetaphosphate (TP),

(b) Structures of amino acids and peptide (stable string) products.

(c) Summary of the experimental protocol. Glycine and alanine are dissolved in water, the solution pH is set, and mixtures are incubated, open to the atmosphere, at different temperatures for 24 hours, which in most cases promotes evaporation and leave a reactive dry solid-phase. Samples are then re-dissolved in water and analyzed by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) as well as mass spectrometry (MS).

(d) HPLC chromatograms of the starting amino acids and identified peptide standards.

(e) MS/MS spectrum of species having the same composition (G2 A) but different sequences exhibit different mass fragmentation patterns with distinct sequence-specific product ions, which enable characterization of peptide sequences.

For more details, see Sibilska et al. 2018.